BY: YAW MARFO ADU

Almost every incumbent lost in the 2024/25 election cycle. Only Canada and Australia defied the trend and even then, it was less a triumph of governance than a misstep by their opponents. In both countries, opposition parties borrowed from Donald Trump’s playbook, with some even calling him as an ally. Ironically, it was Trumpism that cost Sussan Ley and Pierre Poilievre their elections.

This global revolt against incumbents reached even the most stable democracies. Take Botswana: after 54 uninterrupted years in power, the Botswana Democratic Party finally fell in 2024.

The roots of this fatigue were economic. Inflation, unemployment, and a message of erroneous governance united voters across continents. When ten cedis buy you less rice than they did a year ago, and jobs are scarce, it’s easy to believe the government has failed you. Even as economic indicators began improving by late 2024, the political damage was already sealed.

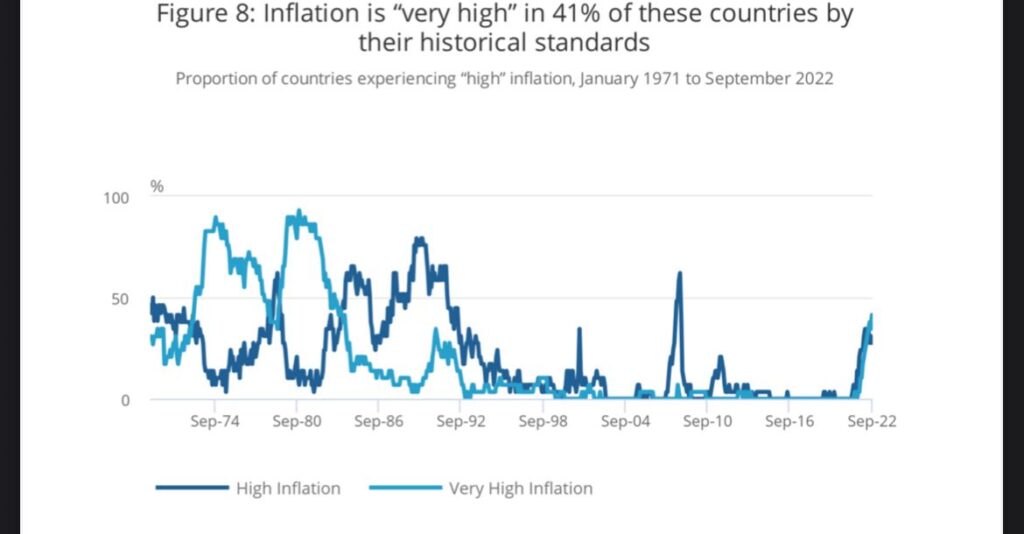

According to the UK’s Office for National Statistics, 41% of 21 countries experienced “very high” inflation in September 2022, while another 28% faced “high” inflation. More than half the world’s economies endured such pressures for months, levels unseen since the early 1990s. The cost-of-living crisis became the universal campaign issue, and incumbents everywhere paid the price.

But tides in politics turn as fast as they crash. In the UK, Labour’s massive victory already feels fragile. In the United States, Donald Trump’s approval ratings are the lowest ever recorded for a president. Ghana’s President Mahama faces a similar slide in public enthusiasm. Across nations, the question now isn’t who fell, but who will rise first.

History suggests the comebacks will come. Yet the biggest obstacle isn’t public anger but rather it’s internal division. As Democratic strategist Mike Nellis put it, “We are a party out of power without a standard-bearer, and that isn’t going to change until the presidential election.” Every party goes through this disoriented phase after defeat.

In Ghana, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) seems to have read the moment well. By scheduling its next presidential primary 13 months after its 2024 defeat, the NPP hopes to end factional rifts early and refocus on rebuilding two years ahead of the 2028 polls. Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia is widely seen as the frontrunner, and his campaign message of unity has struck a chord within the party. If he wins, it could give the NPP its best chance yet to close ranks and restore coherence after a bruising loss, a vital step toward any credible comeback. It’s a pragmatic recognition that disunity, not defeat, is the real disease.

The global wave of incumbency fatigue in 2024/25 was not just a rejection in of governments, but a referendum on economic pain and public disillusionment. Yet politics, like economics, moves in cycles. The same frustration that swept incumbents out of power could just as easily propel them or their successors back in once unity returns. From Washington to Gaborone to Accra, the real test is not how spectacularly parties fell, but how swiftly they rebuild trust and purpose. The comeback, after all, begins the moment the fighting stops.